Carl Millner Gallery – Romantic landscape painting

The acquisition of a painting by Carl Millner in the 1970s laid the foundation for Mindelheim’s comprehensive collection of works by this eminent landscape painter, a member of what is now known as the “Munich School”.

Thanks to the generous support of numerous sponsors such as the Sparkassenstiftung Memmingen-Mindelheim, the Sparkassenstiftung Mindelheim, the Volksbank-Memmingen-Stiftung, VWEW-Energie, the Förderkreis der Mindelheimer Museen e.V. as well as private benefactors, the town of Mindelheim has been able to continuously expand its collection of paintings, watercolours, drawings and sketches since the 1990s. By 2012, the collection had grown to the point where an art gallery could be opened in the museum’s special collection, now housed in the former Jesuit College building.

Before 2018, hardly anything was known about the biography of Carl Millner. Sources which had been archived by Millner’s descendants up to that point let the person of Carl Millner come alive for the first time. These new findings were incorporated into the newly-conceived Carl Millner Gallery in 2018.

Carl Millner Gallery

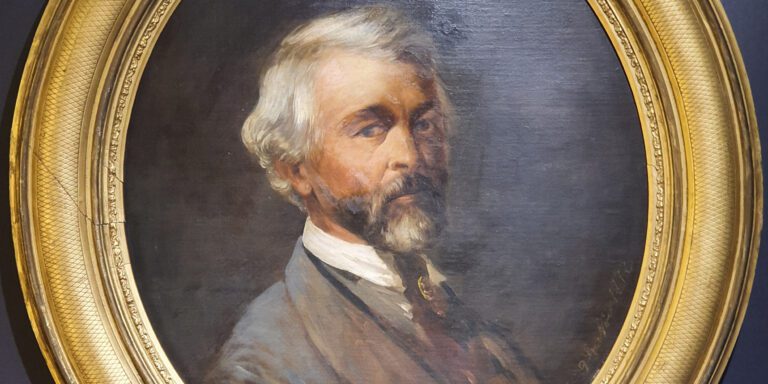

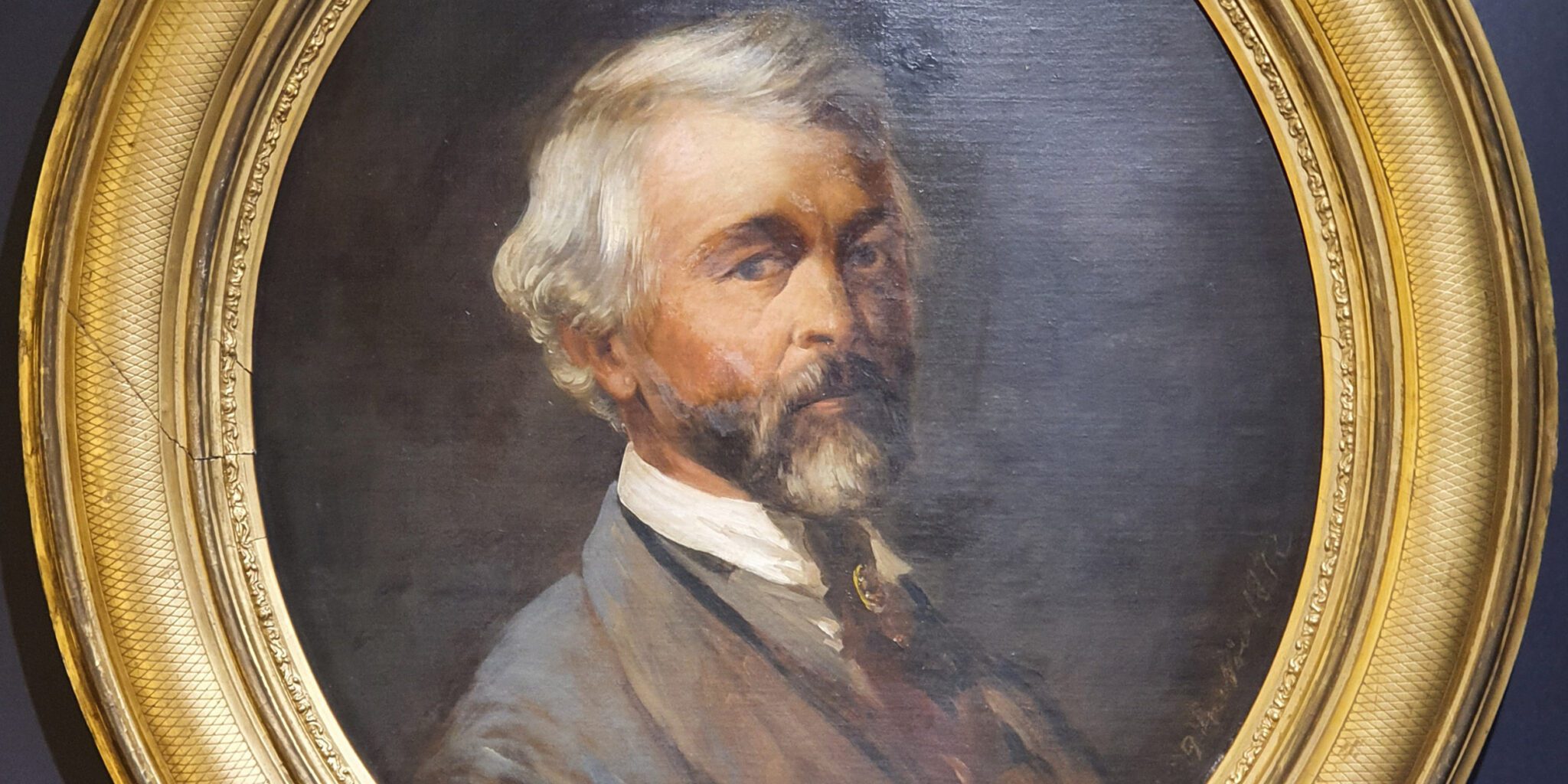

Carl Millner

Carl Millner was born in Munich in 1825. In 1840, he trained at the Polytechnic School of Drawing in preparation for his studies at the Munich Academy, which he attended from 1841 to 1846.

Following this, Millner went on a study trip that took him to Switzerland and Austria. During the 1850s, he went on walking tours to Tyrol and Lower Bavaria and made several trips to Italy.

In 1858, Millner established an atelier in Munich.

In 1859, King Ludwig I acquired the first painting for the Neue Pinakothek. Many commissions from the Wittelsbach dynasty and Emperor Franz Josef were to follow. The interest of high noble circles sparked an extremely creative and productive period in Carl Millner’s career. His atelier developed to become a flourishing business, in which he carried out commissioned work for a circle of local buyers and others. His paintings were already being sold to England and America in the 19th century.

Carl Millner died in Munich in 1895.

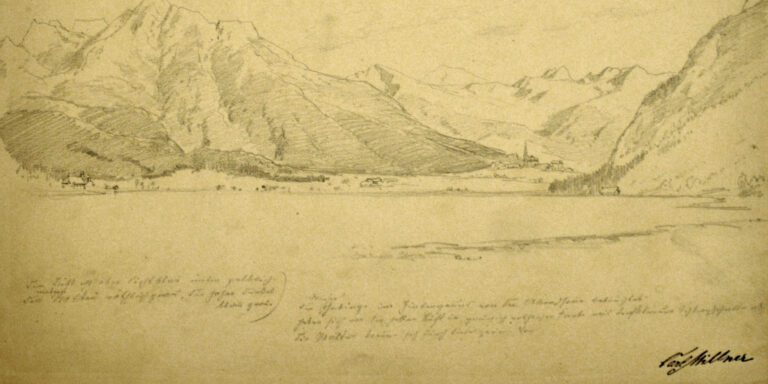

Graphics

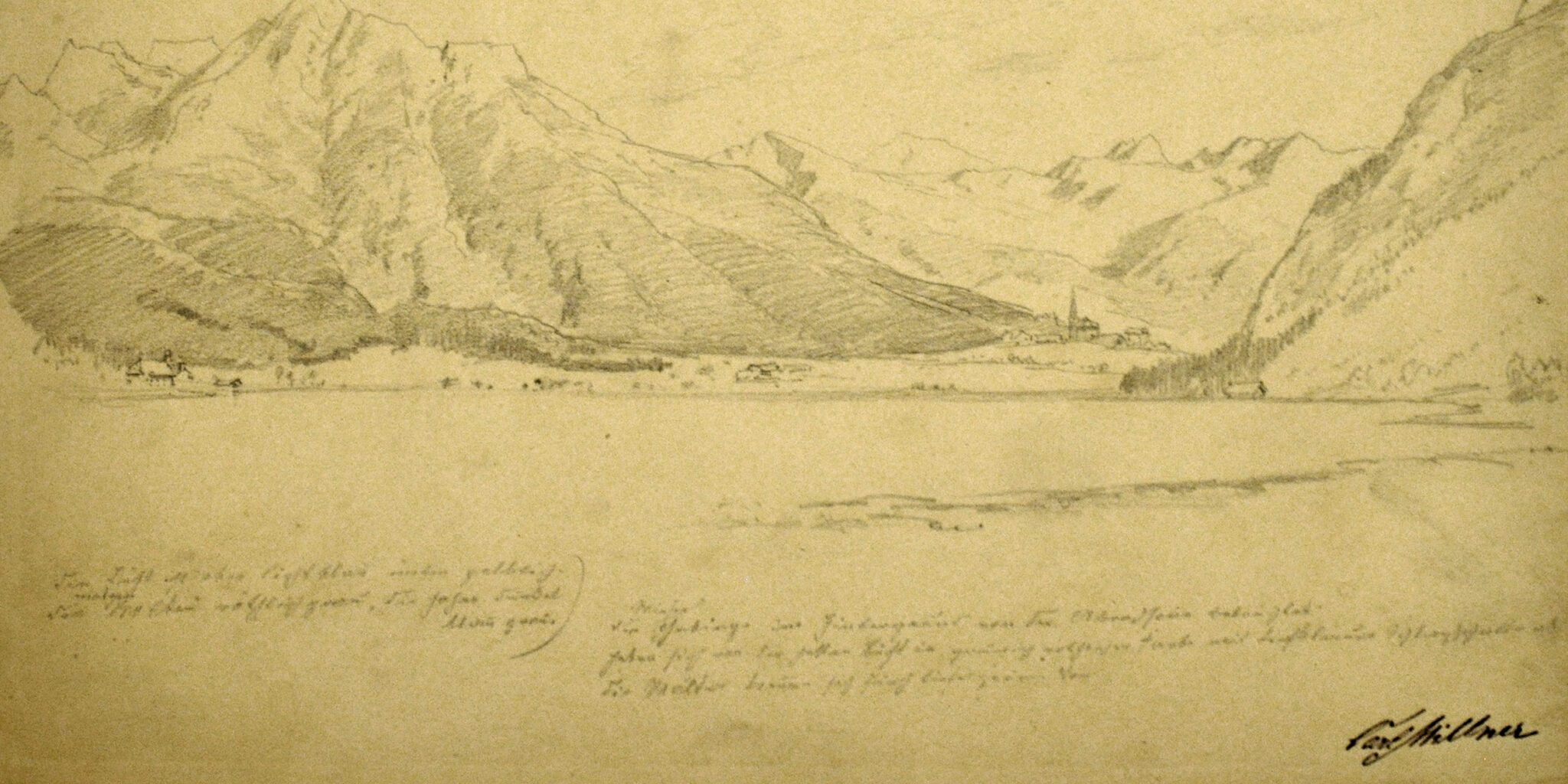

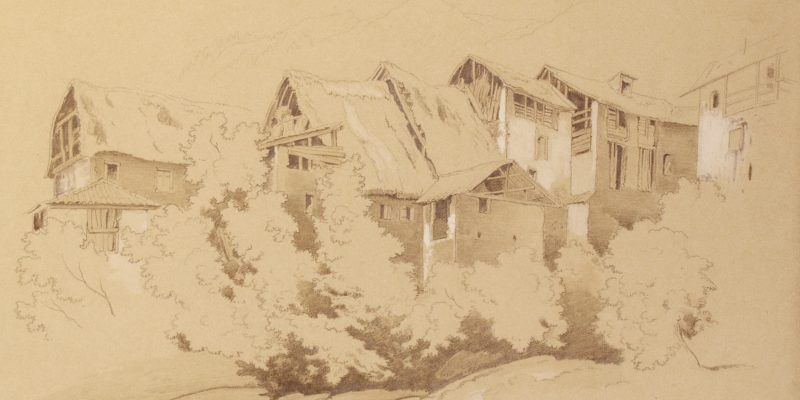

Especially in the period after completing his studies, Millner undertook several journeys, which took him from Holland to Sicily. He recorded his travel impressions in pencil and charcoal drawings. Most of the drawings were done in mountain regions and show mountain ranges, rock formations, wild torrents and mountain lakes.

Some of them are quickly executed sketches – like a vague snapshot done with only a few strokes. Other drawings are more detailed and are accompanied by Millner’s notes on the colours and lighting conditions that prevailed at the moment of drawing. In order to recall the colour moods later when working in his studio, Millner coloured some drawings in translucent watercolours.

Millner’s sketch books also contain detailed drawings that emphasise not so much the outlines, but the interaction of light and dark, making them appear very much like paintings.

Paintings

In the mid-19th century, landscape painting was characterised by seemingly realistic reproductions of nature. However, these paintings were not naturalistic portraits of the landscape. Instead, they depicted landscapes that united specific mountains and mountain ranges to create an ideal composition.

At that time, the young artists of the Munich School, to which Carl Millner also belonged, wandered through the Munich countryside and the Alps and executed drawings as an aid to memory that later formed the basis for the oil paintings created in the studio.

Carl Millner’s paintings are staged works based on various sketches and drawings. In very rare cases, does a single drawing correspond to an entire painting – as in this work entitled “The painter and the Matterhorn”. Carl Millner generally compiled individual motifs taken from many sketches like movable pieces of scenery to create a new composition.

Motifs of Romanticism

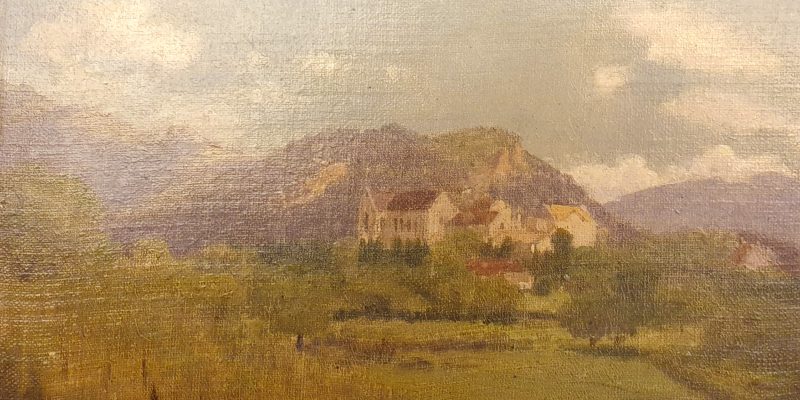

It was not until around 1840 that romantic tendencies increasingly found their way into the paintings of the Munich School. Examples of this are seen in the artists’ preoccupation with fairy tales, myths and legends, or their predilection for mediaeval castles and towns.

Mediaeval buildings and artificial ruins erected during the Romantic period corresponded to the aesthetics of decay popular in this artistic genre. Carl Millner’s work entitled “Magdalene hermitage in the gardens of Nymphenburg Palace” is a depiction of an artificial ruin.

The oil sketch “Mediaeval monastery in Italy” relates to the Middle Ages, seen as a romantically transfigured, idealised past. This sketch also epitomises the longing for Italy, which was regarded as the essence of higher education. Numerous drawings of Italian landscapes bear witness to Millner’s walking trips through Italy, which had been considered an integral part of an artistic education since Renaissance times.

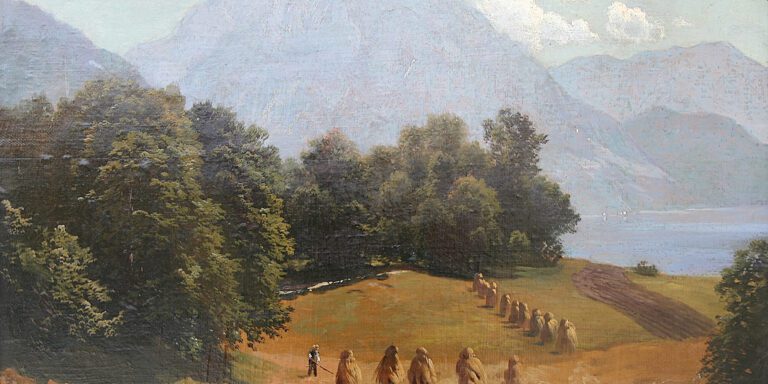

Idealised country life

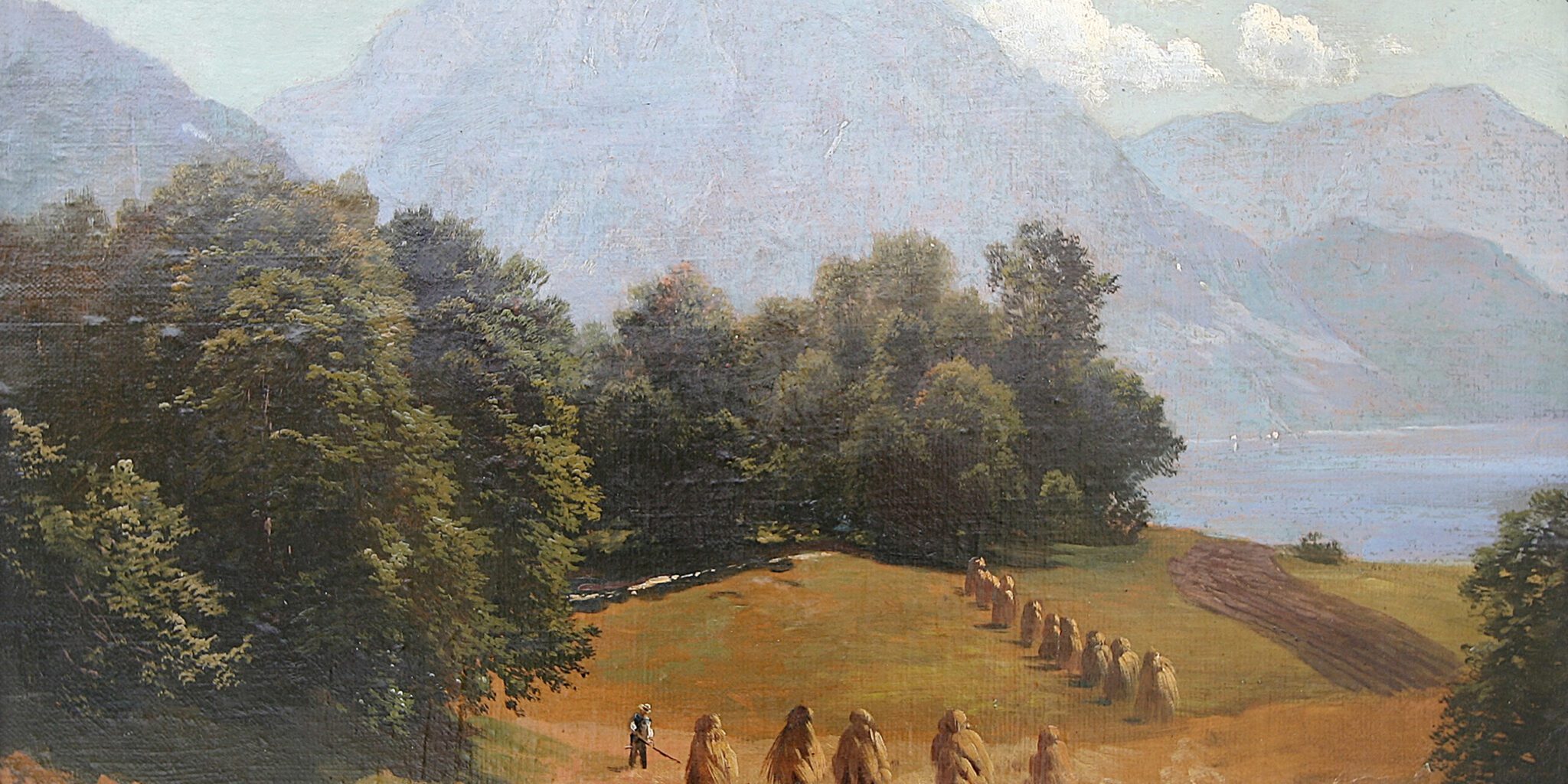

At the beginning of the 19th century, the view of nature changed, as did the perception of rural life. In contrast to an urban existence, life in the countryside seemed natural and unspoilt. The painters of the Munich School created works depicting the countryside around Munich and village scenes, which contrasted with paintings of high mountain landscapes.

A gradually increasing interest in nature led to scientific research into the subject. The observation of weather phenomena, the classification of plants and animals, as well as geological studies further encouraged this enthusiasm for nature and, in turn, landscape painting. At that time, the high mountains were still unexplored territory and therefore a highly topical motif for painters. The rise of alpinism and early tourism attracted daring mountaineers to the high regions. However, most of these early tourists preferred to travel to the countryside for their summer retreat.

Alpine themes

“… in 54, 56 and 57, I went to Northern Italy where I also did some paintings. But my preference for German mountain landscapes replaced the Italian motifs and I devoted all my studies to this subject” (Carl Millner).

Mountain landscapes with waterfalls and rushing torrents were among the preferred themes of the Munich School. The depiction of a seemingly unconquerable elemental force was just as popular as the contrasting theme of nature tamed by man – as shown by mills, for example.

Carl Millner’s most frequently chosen motif depicts dramatic high mountain landscapes with snow-covered peaks or craggy rock formations, showing nature in its primal state. Many of his high alpine landscapes are set under a clouded sky. These thundery moods are a theatrical staging of nature, expressing the unpredictability of the mountain world.

Lighting moods

We cannot ignore Carl Rottmann’s influence on Millner’s painting in regard to the use of lighting. Following his example, Millner masterfully staged the contrasting light of sunrise and sunset. Another light phenomenon used by Millner in his painting is “Alpenglühen”, the glow of the Alps. While the valley lies in twilight shadows, the mountain ridge appears in a glow of pink.

However, a particular challenge in terms of lighting is demonstrated in the depiction of a landscape in sallow moonlight. Mysterious moonlit nights were a central theme amongst the artists of the Romantic period and found expression above all in poetry. This theme is comparatively rare in the paintings of the day, due to the technical difficulties involved in depicting a nocturnal landscape. The absence of light compels the painter to resort to a minimal palette of colours, thus demonstrating Millner’s absolute mastery.